As we dive into San Diego Junior Theatre’s first production of 2025, Churlish Chiding of Winter Winds: A Shakespeariment, director David Goodwin has shared more about his background in the theatre, his career highlights, his lifelong connection to Shakespeare’s work, and more details about how he created this new and exciting world-premiere production.

One exposure to Shakespeare that made a strong impression on me was my Freshman year in the Dramatic Writing program at NYU in a class called Shakespeare for Writers. We worked through a play a week, which was an accelerated pace, but in many ways made it easier- they are after all, plays, and they are intended to be digested in a single, focused sitting. To this day, if I’m reading one of Shakespeare’s plays, I prefer to read it in a single session if possible.

Each play is a self-contained world, and being immersed in so much of the canon in a focused manner made my world much bigger.

[After school], as an actor, one of the biggest assets I had was that I knew plays. Those two years in playwriting school gave me a solid knowledge of Shakespeare – so I could walk into an audition knowing the play and knowing what character I would be best for, which is an enormous asset.

I had done maybe four shows when I got cast to play Hal in Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 at Shakespeare Dallas. I was elated at being cast but that quickly turned to frustration and anxiety over lacking most of the requisite skills to perform the part. I knew Shakespeare, but had no experience performing it. Somehow the Artistic Director believed in me enough to cast me, but doing the show felt like drowning every night. I went home feeling that the play had defeated me, and that the skills I needed to perform well was a vast body of knowledge that would take years to acquire. I was, however, surrounded by older actors who knew what they were doing. The late, great Lynn Mathis played my father, Henry, and he was a major role model for me. The King and Hal have a lot of extended scenes together and it was a master class in every aspect of Shakespearean performance: how to be physically and vocally expansive enough to play the characters and fill the space while staying authentic. I also simply had no idea a human body could produce as much sound as he could without amplification.

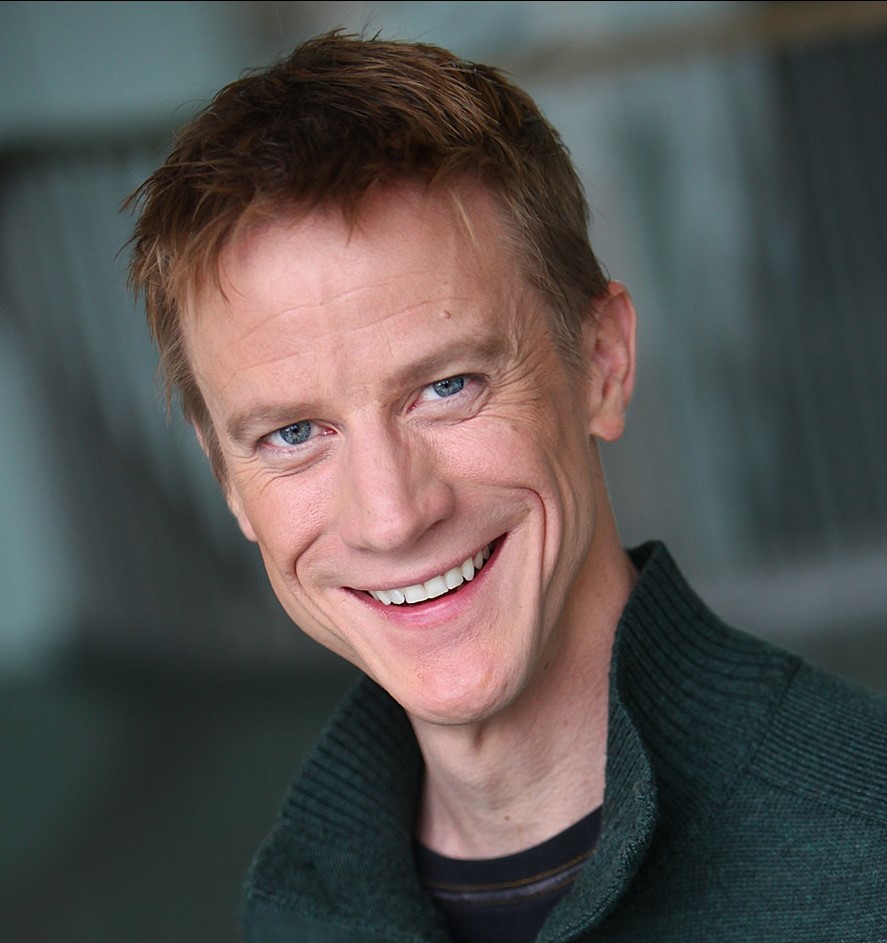

As a performer, some of the highlights of my career would be playing Iago in Othello (see photos below) and Edgar in King Lear. Iago is wonderful because he’s such a complete character– there’s always more there to discover no matter how deep you dig. Edgar is enormous fun because of the transformation you get to make into poor Tom. The character disguises himself vocally and physically to such a degree that his own family doesn’t recognize him, which is an awesome challenge for a performer.

That initial deep dive [playing Hal] got me hooked on the complete mind, body, spirit workout of a Shakespearean performance and made me want to excel at it. This led me to pursue training with Tina Packer at Shakespeare and Co. off and on over the next several years.

Through my work as a teaching artist, I received a fellowship where I was given a group of students and free reign to bring anything into the classroom that I felt would fuel engagement with the arts. This led to me to adapt some of the First Folio pedagogy I had learned from Shakespeare and Co. for use with middle school students. In 2015 I was trying to get funding for an arts education collaboration with Shakespeare Dallas, which required me to present my student’s work. In almost every single presentation session, feedback would involve someone saying something like “I can understand your students better than when I go see professional Shakespeare productions.” They weren’t referring to diction or projection, but the meaning of the lines being clearly delivered in the performance.

My students did not have a better grasp of what they were saying compared to adult actors, but they had all been trained in how to play the music of the verse above everything else, which goes a long way towards making the performance comprehensible. Shakespeare Dallas offered me to be their Director of Training shortly thereafter and I remained in that role until I moved to San Diego in 2019; Shakespeare has consistently stayed at the center of my work ever since.

I directed a production of Much Ado About Nothing my first year as a full-time teacher, which ended up being really rewarding. This was in Texas where the U.I.L. Competition is a big focus for drama departments; we ended up winning first place that year for our district, which I don’t think any of my students or myself considered to be among the possible outcomes of competing. One student in particular was recognized for his performance who was among those I practically pushed onstage.That experience stuck with me and I’m much more proactive now about trying to get students into the spotlight when I feel like I glimpse some potential, even if they don’t see it in themselves yet.

I teach Shakespeare as part of my day job. I’m currently in charge of Performing Arts at e3 Civic High, the school housed in the San Diego Central Public Library. The English Speaking Union National Shakespeare Competition has become a tradition at our school in the five years I’ve been there. We’ve also done a number of Shakespeare mainstage productions. We do a pretty deep dive into Shakespeare to prepare for the monologue competition, but the plays that we produce are largely chosen based on student input. There have been multiple years where students have wanted to do Shakespearean plays for the mainstage shows.

I became the director for this project through my continued work with Junior Theatre. I met (former Executive Director) Jimmy Saba not long after moving here. My wife is a teacher here and I think one of her students was performing in a Junior Theatre production. Jimmy did his graduate work at SMU in Dallas and we have a number of mutual acquaintances. Maybe two and a half years ago I started teaching camps and the occasional weekend workshop, much of which was Shakespeare-related. The idea of doing a devised work using Shakespeare’s winter-themed writings was not something I came up with, it was in the season before I became associated with it. I think I happened to be running a Shakespeare camp around the time Junior Theatre was looking for a director for the project and I jumped at the chance when it was offered.

Devising work is a unique challenge. Putting a nonexistent show in your season schedule is a remarkably effective way to produce new work. I think it’s much more challenging for many of the actors in the show because it’s such a unique process and many of them haven’t done anything like it. We have a few veterans of the devised Edgar Allen Poe show SDJT did a few years ago in the cast, which was really helpful. The devising process requires an enormous amount of trust as the actors must trust that there will be a show at the end.

In preparation for this production, I began by pulling all the references to winter in Shakespeare that I was aware of and seeing if there was any thread connecting them. Once I had that material, I began to dig into the canon to find more winter-related works. It turns out that some of the most direct commentary on the theme of winter is found in the sonnets, which I am far from an expert on. I quickly concluded that the show would need to expand to be a broader reflection of Shakespeare’s work on the seasons and time, with winter being the centerpiece. When Shakespeare addresses winter, the association is universally negative, equating winter with the destructive capacity of time. In Shakespeare’s worldview summer represents youth and promise while winter represents old age and reckoning. In order to devise a show that wasn’t too bleak, I felt like we would need to see winter turn back into spring and see the renewal of life that winter is the cost of (in the same way that one might say death is the price of being born). Once that framework was in place I was led into an exploration of Shakespeare’s pastoral plays as that is where one finds the most direct treatment of the seasons. Pastoral was a popular form in Shakespeare’s time that presented an idyllic life in nature as a response to the often crowded, dirty, and dangerous aspect of urban life. The key theme in the pastoral form is that we suffer and become distorted versions of ourselves when we become estranged from the natural world to which we belong. Thematically, this seemed like rich territory to explore in our current moment, when our relationship with nature seems to be at the forefront of discussions about humanity’s future. Also, the notion of living within an order and set of rhythms that are isolated from the natural world is something that I think many young people can relate to. The self-consciousness, superficiality, paranoia, and hyperbolic reactivity that Shakespeare associated with toxic court settings in plays such as As You Like It are qualities that are in no short supply in the online ecosystem of social media where young people spend much of their time. You really couldn’t come up with a better single sentence summation of pastoral then “go touch grass.”

The eagerness and excitement that everyone brought to rehearsals was tremendous. Any notion that we would have difficulty coming up with material was quickly banished. The ensemble continued to impress me with the sheer abundance of ideas that were put forward every rehearsal.

In terms of training actors in Shakespearean performance, I think you can often work more efficiently with young actors than with professionals. Much of the work I do is very technical – where to breathe on the line, which word to lift, which word to expand, etc. Actors trained in contemporary performance technique can sometimes resist that type of work because they feel like you’re giving them a line reading. Generally, young actors haven’t acquired fixed ideas of what preparing a performance is supposed to look like, so when I tell them to lift a particular word, they try it, intuitively hear that the meaning of the line is carried more clearly, and adopt it. The trick is to maintain those technical elements, to “play the music” but still bring your personal truth to the character. Ultimately the performance can be technically perfect but if there’s not a personal connection between the actor and the text, the performance might solicit admiration from the audience, but is unlikely to move them.

Working on this current show feels like a culmination of the last few decades because we’re drawing on so many different plays for the production. I’ve done a lot of different things and worn a lot of different hats as a theater artist: actor, director, playwright, puppeteer, and educator. Churlish Chiding of Winter Winds, perhaps more than anything I’ve been involved in, is providing an opportunity to synthesize all of those elements in some capacity. I feel like I’ve been preparing for this production for most of my professional life.

Churlish Chiding of Winter Winds: A Shakespeariment runs from through January 19 at the Casa del Prado Theatre in Balboa Park. Tickets available here.